| Home | Accessory Kit | Marsh CD Collection | Library | Contact Us |

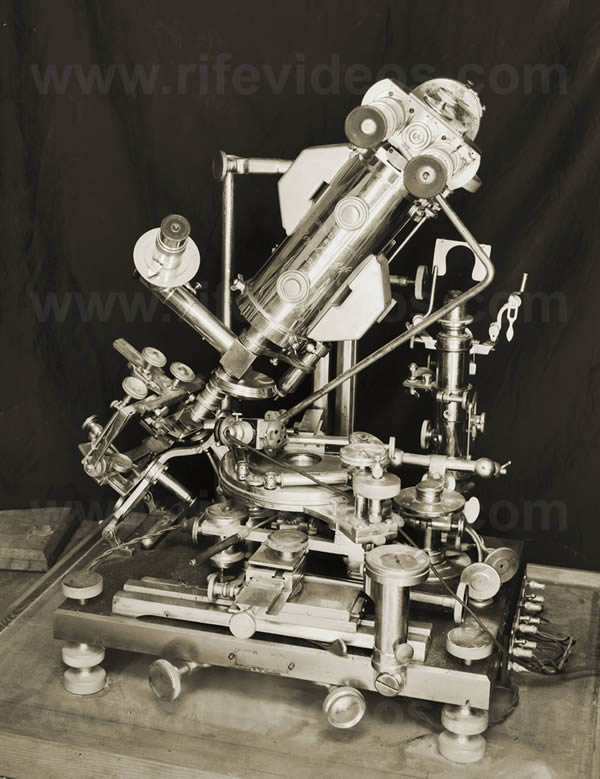

Universal Microscope |

|

Principle of Parallel Rays THE UNIVERSAL MICROSCOPE The Universal Microscope, which is the largest and most powerful of the light microscopes, developed in 1933, consists of 5,682 parts. This microscope derives its name from its adaptability to all fields of microscopical work. The microscope is fully equipped with separate sub stage condenser units for transmitted and monochromatic beam, dark-field, polarized, and slit-ultra illumination and includes a special device for crystallography. The entire optical system of lenses and prisms as well as the illuminating units are made of block-crystal quartz. The illuminating unit used for the examination of the filterable form, of disease organisms contains 14 lenses and prisms, three of which are in the high-intensity incandescent lamp, four in the Risley prism, and seven in the achromatic condenser system. Two circular, wedge-shaped prisms are suspended between the source of light and the specimen being examined. The two prisms are used for changing the angle of incidence of the light passing through the specimen being examined. When the light passes through these prisms, it is divided or split into two beams, one of which is refracted to such an extent that it is reflected to the side of the prism while the second beam is permitted to pass through the prism and illuminate the specimen owing to its chemical constituents. The mounting arrangement on the universal microscope permits each of the two prisms to be rotated in opposite directions by a vernier control throughout 360 degrees. This vernier adjustment permits bending the transmitted beam of light at variable angles of incidence while, at the same time, a small portion of the spectrum is projected into the axis of the microscope owing to the chemical constituents of the microorganism. The vernier adjustment permits only a small portion of the spectrum to be visible at any one time, but it is possible to select any portion from one end of the spectrum to the other. When that portion of the spectrum is reached where both the organism and the color band vibrato in exact accord, a definite characteristic spectrum is emitted by the organism. In the case of the filter-passing form of the Bacillus Typhosus a turquoise blue color is emitted and the plane of polarization deviated plus 4.8 degrees. The predominating chemical constituents of the organism are next ascertained after which the quartz prisms are adjusted by means of the vernier control to minus 4.8 degrees so the opposite angle of refraction may be obtained. A monochromatic beam of light corresponding exactly to the frequency of the organism is then passed through the specimen along with the direct transmitted light. This beam permits the observer to view the organism stained in its true chemical color and reveals its own individual structure in a field which is brilliant with light. The rays of light refracted by the specimen enter the objective lens and are carried up the tube in parallel rays through 21 (twenty-one) light bonds to the ocular Iens. A tolerance of less than one wave length of visible light is permitted in the core beam of illumination. In the standard optical microscope, the light rays tend to converge as they rise higher and finally cross each other, arriving at the ocular lens, separated by a considerable distance. In the Rife microscopes, as the rays are about to cross each other, a specially designed quartz prism is inserted which servos to separate the light rays to a near parallel line again. Additional prisms are inserted each time the rays are ready to cross. These prisms, located in the tube, are adjusted and held in adjustment by micrometer screws in special tracks made of magnelium, a metal having the closest expansion coefficient of any metal to quartz. These prisms are separated by a distance of only 30 millimeters. Thus, the greatest distance that the image in the universal microscope is projected through any one media either quartz or air is 30 millimeters instead of the 160 to 190 millimeters employed in the air-filled type of the ordinary microscope. It is this principle of parallel rays in the Universal Microscope and the resultant shortening of projection distance between any two blocks or prisms plus the fact that objectives can thus be substituted for oculars, these "oculars" being three matched pairs of ten-millimeter, seven-millimeter, and four-millimeter objectives in short mounts, which make possible not only the unusually high magnification and resolution but which serve to eliminate all distortion as well as all chromatic and spherical aberration. The Universal stage is a double rotating stage graduated through 360 degrees in quarter minute arc divisions, the upper segment carrying the mechanical stage having a movement of 40 degrees, the body assembly which can be moved horizontally over the condenser also having an angular tilt of 40 degrees plus or minus. Heavily constructed joints and screw adjustments maintain rigidity of the microscope which weighs two hundred pounds and stands twenty-four inches high, the bases of the scope being nickel cast-steel plates, accurately surfaced, and equipped with three leveling screws and two spirit levels set at angles of 90 degrees. The coarse adjustment, a block thread screw with forty threads to the inch, slides in a one and one-half dovetail which gibs directly onto the pillar post. The weight of the quadruple nosepiece and the objective system is taken care of by the intermediate adjustment at the top of the body tube. The stage, in conjunction with a hydraulic lift, acts as a lever in operating the fine adjustment. A six-gauge screw having a hundred threads to the inch is worked through a gland into a hollow, glycerin-filled post, the glycerin being displaced and replaced at will as the screw is turned clockwise or anticlockwise, allowing a five-to-one ratio on the lead screw. This, accordingly, assures complete absence of drag and inertia. Working together back in 1931 and using one of the smaller Rife Microscopes having a magnification and resolution of 17,000 diameters, Dr. Rife and Dr. Arthur Isaac Kendall of the Department of Bacteriology of Northwestern University Medical School were able to observe and demonstrate the presence of the filter-passing forms of Bacillus Typhosus. An agar slant culture of the Rawlings strain of Bacillus Typhosus was first prepared by Dr. Kendall and inoculated into six cubic centimeters of "Kendall” K Medium, a medium rich in protein but poor in peptone and consisting of one hundred mg. of dried hog intestine and 6 cc. of tyrode solution (containing neither glucose nor glycerin) which mixture is shaken well so as to moisten the dried intestine powder and then sterilized in the autoclave, fifteen pounds for fifteen minutes, alterations of the medium being frequently necessary depending upon the requirements for different organisms. Now, after a period of eighteen hours in this K Medium, the culture was passed through a Berkefeld "W' filter, a drop of the filtrate being added to another six cubic centimeters of K Medium and incubated at 37 degrees centigrade. Forty-eight hours later this same process was repeated, the "N" filter again being used, after which it was noted that the culture no longer responded to peptone medium, growing now only in the protein medium. When again, within twenty-four hours, the culture was passed through a filter - the finest Berkefeld “W” filter, a drop of the filtrate was once more added to six cubic centimeters of K medium and incubated at 37 degrees centigrade, a period of three days elapsing before the culture was transferred to K Medium and yet another three days before a new culture was prepared. When, viewed under an ordinary microscope, these cultures were observed to be turbid and to reveal no bacilli whatsoever. When viewed by means of darkfield illumination and oil immersion lens, however, the presence of small, actively-motile granules was established, although nothing at all of their individual structure could be ascertained. Another period of four days was allowed to elapse before these cultures were transferred to K Medium and incubated at 37 degrees centigrade for twenty-four hours when they were then examined under the Rife Microscope where, as was mentioned earlier the filterable typhoid bacilli, emitting a blue spectrum, caused the plane of polarization to be deviated plus 4.8 degrees. Then when the opposite angle of refraction was obtained by means of adjusting the polarizing prisms to minus 4.8 degrees and the cultures illuminated by a monochromatic beam coordinated in frequency with the chemical constituents of the typhoid bacillus, small, oval, actively-motile, bright turquoise-blue bodies were observed at a magnification of 5,000 diameters, in high contrast to the colorless and motionless debris of the medium. These observations were repeated eight times, the complete absence of these bodies in uninoculated control K Media also being noted. Examinations of gram and safranin stained films of cultures of Bacillus Typhosus, gram and safranin stained films of cultures of the streptococcus from poliomyelitis, and stained films of blood and of the sediment of the spinal fluid from a case of acute poliomyelitis were made with the result that bacilli, streptococci, erythrocytes, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and lymphocytes measuring nine times the diameter of the same specimens observed under the Zeiss scope at a magnification and resolution of 900 diameters, were revealed with unusual clarity. Seen under the darkfield microscope were moving bodies presumed to be the filterable turquoise-blue bodies of the typhoid bacillus which, as Dr. Rosenow has declared in his report ("Observations on Filter-Passing Forms of Eberthella Typhi Bacillus Thphosus--and of the streptococcus from Poliomyelitis," Proceedings of the Staff Meetings of the Mayo Clinic, July 13,1932), were so "unmistakably demonstrated" with the Rife Microscope, while under the Zeiss scope stained and hanging drop preparations of clouded filtrate cultures were found to be uniformly negative. With the Rife Microscope also were demonstrated brownish-gray cocci and diplococci in hanging drop preparations of the filtrates of streptococcus from poliomyelitis. These cocci and diplococci, similar in size and shape to those seen in the cultures although of more uniform intensity, and characteristic of the medium in which they had been cultivated, were surrounded by a clear halo about twice the width of that at the margins of the debris and of the Bacillus Typhosus. Stained films of filtrates and filtrate sediments examined under the Zeiss microscope, and hanging drop, dark-field preparations revealed no organisms, however. Brownish-gray cocci and diplococci of the exact same size and density as those observed in the filtrates of the streptococcus cultures were also revealed in hanging drop preparations of the virus of poliomyelitis under the Rife Microscope, while no organisms at all could be seen in either the stained films of filtrates and filtrate sediments examined with the Zeiss scope nor in hanging drop preparations examined by means of the dark-field. Again using the Rife Microscope at a magnification of 8,000 diameters, numerous non-motile cocci and diplococci of a bright-to-pale pink in color were seen in hanging drop preparations or filtrates of Herpes encephalitic virus. Although these were observed to be comparatively smaller than the cocci and diplococci of the streptococcus and poliomyelitic viruses, they were shown to be of fairly even density, size, and form and surrounded by a halo. Again, both the darkfield and Zeiss scopes failed to reveal any organisms, and none of the three microscopes disclosed the presence of such diplococci in hanging drop preparations of the filtrate of a normal rabbit brain. Dr. Rosenow has since revealed these organisms with the ordinary microscope at a magnification of 1,000 diameters by means of his special staining method and with the Electron Microscope at a magnification of 12,000 diameters. Dr. Rosenow has expressed the opinion that the inability to see these and other similarly revealed organisms is due, not necessarily to the minuteness of the organisms, but rather to the fact that they are of a non-staining, hyaline structure. Results with the Rife Microscopes, he thinks, are due to the "ingenious methods employed rather than to excessively high magnification." He has declared also, in the report mentioned previously, that “Examination under the Rife Microscope of specimens containing objects visible with the ordinary microscope, leaves no doubt to the accurate visualization of objects or particulate matter by direct observation at the extremely high magnification obtained with this instrument." Experiments conducted in the Rife Laboratories have established the fact that these characteristic diplococci arefound in the blood monocytes in 92 per cent of all cases of neoplastic diseases. It has also been demonstrated that the virus of cancer, like the viruses of other diseases, can be easily changed from one form to another by means of altering the media upon which it is grown. With the first change in media, the B.X. virus becomes considerably enlarged although its purplish-red color remains unchanged. Observation of the organism with an ordinary microscope is made possible by a second alteration of the media. A third change is undergone upon asparagus base media where the B.X. virus is transformed from its filterable state into cryptomyces pleomorphia fungi, these fungi being identical morphologically both macroscopically and microscopically to that of the orchid and of the mushroom. And yet a fourth change may be said to take place when this cryptomyces pleomorphia, permitted to stand as a stock culture for the period of metastasis, becomes the well-known mahogany-colored Bacillus Coli. In other words, the human body itself is chemical in nature, being comprised of many chemical elements which provide the media upon which the wealth of bacteria normally present in the human system feed. These bacteria are able to reproduce. They, too, are composed of chemicals. Therefore, if the media upon which they feed, in this instance the chemicals or some portion of the chemicals of the human body, becomes changed from the normal, it stands to reason that these same bacteria, or at least certain numbers of them, will also undergo a change chemically since they are now feeding upon a media which is not normal to them, perhaps being supplied with too much or too little of what they need to maintain a normal existence. They change, passing usually through several stages of growth, emerging finally as some entirely new entity--as different morphologically as are the caterpillar and the butterfly (to use an illustration given us). The majority of the viruses have been definitely revealed as living organisms, foreign organisms it is true, but which once were normal inhabitants of the human body--living entities of a chemical nature or composition. Under the Universal Microscope disease organisms such as those of tuberculosis, cancer, sarcoma, streptococcus, typhoid, staphlococcus, leprosy, hoof and mouth disease, and others may be observed to succumb when exposed to certain lethal frequencies, coordinated with the particular frequencies peculiar to each individual organism, and directed upon them by rays covering a wide range of waves. With the aid of its new eyes--the new microscopes, all of which are continually being improved--Science has at last penetrated beyond the boundary of accepted theory and into the world of the viruses with the result that we can look forward to discovering new treatments and methods of combating the deadly organisms--for Science does not rest. One or the most important questions in the minds of those who come in contact with the RIFE FREQUENCY INSTRUMENTS is: Why doesn’t the frequency or coordinative resonance in tune with the microorganism destroy the cell in which it lives? The answer is this: Because the chemicals making up the human cell are not of the same constituency as the microorganism; therefore, the power of the instrument designed to devitalize the microorganism only is a great deal less in power than would be necessary to devitalize a human cell, mainly because the frequency number is different. For example: many automobiles today appear in different shapes and sizes and powers. The power produced by a smaller car is perhaps a fraction of the power produced by a larger car, even though they are all cars. Similarly, the microorganism lives within the cell, which perhaps contains the same chemicals of which the microorganism is made, but each has different molecular structural quantities. Thus, the microorganism is devitalized and the area in which it lived is unaffected by this coordinative resonance. |